Banyan

The trouble with democracy

With varying degrees of justification, election boycotts are in vogue in Asia

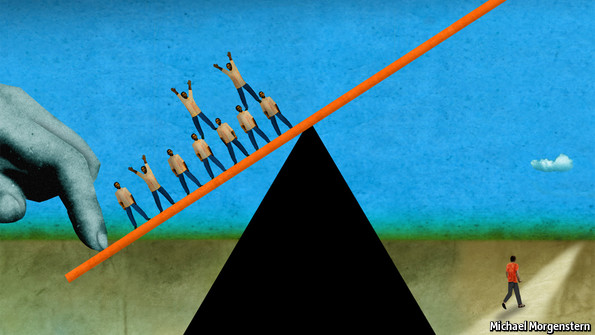

THOSE living in dictatorships often harbour the delusion that the point of democracy is that you get the government you want. Those living in democracies soon realise that is not the system’s most salient feature: rather, it is that a large number of voters get the government they do not want and are expected to put up with it until the next election. In many young democracies, politicians find this hard to accept. So governments rig elections to make sure they win; and opposition parties reject elections they think they will lose.

For combinations of these two reasons, Asia is experiencing a wave of election boycotts. The poll held on January 5th in Bangladesh was a foregone conclusion after the opposition refused to take part. In Nepal 33 parties rejected a constituent-assembly election in November, including one faction of the once-ruling Maoists, who staged a menacing “active boycott”. In Thailand the oldest political party, the Democrats, despite long agitating for dissolution of parliament, is shunning the resulting general election, due on February 2nd. As for those that did contest elections last year, opposition parties in Cambodia and Malaysia are still refusing to accept that they lost. And the tiny Maldives seemed prepared to hold as many elections as it took for the country’s most popular politician, Mohamed Nasheed, to lose.

In this section

Another beating

Bruised, bloodied and probably broken

Stirring the pot

The trouble with democracy

Reprints

Related topics

Democratic Party (United States)

Asia

Maldives

Nepal

Malaysia

The election in Bangladesh was a farce. Because of the boycott, the incumbent Awami League had won a parliamentary majority even before polling stations opened. But the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) did have a strong case that the election would have been farcical even if it had taken part. So deep and bitter is the antagonism between the League and the BNP and their leaders, Sheikh Hasina, the prime minister, and Khaleda Zia of the BNP, that neither has ever trusted the other to run a proper election. Since 1991 governments have had to stand down well before elections, which were held under supposedly neutral caretaker administrations. But after winning a landslide in December 2008, the League used its big parliamentary majority to amend the constitution to do away with this requirement.

Even so, the BNP would probably have contested the election had it maintained the big lead it held up to a few months ago in the opinion polls. But it did not, less because of the memory of how corrupt, high-handed and generally dreadful an administration it ran in 2001-06 than because of the thuggery of some of its supporters. Both sides are to blame for the political violence that has seen some 150 people killed during the campaign and on polling day itself. No incumbent ruling party has ever won a second term in Bangladesh; each election is a victory of hope over experience. After the BNP’s previous term ended, the army stepped in to back a two-year “technocratic” interim administration and to try to build a political system that did not depend on the two “Begums”. It failed. So democracy in Bangladesh remains the fief of two parties that have consistently done all they can to undermine it.

Nepal, in contrast, is enjoying a rare burst of political optimism, after more than five years of fractious stalemate since the previous election in 2008. Despite Maoist threats, turnout in the election was more than 70%. The result was a defeat for the mainstream (non-boycotting) Maoists, whose record in power had bequeathed them the nickname “cashists”. But, despite crying foul because of alleged electoral fraud, they have agreed to join the assembly to draft a constitution. Not much, however, suggests the new assembly will find it easier than its predecessor to find a constitutional settlement all can accept.

Thailand could also do with a new constitution. The current one no longer works. The political system has broken and no one can see the way to devise a new one. The main opposition group, the Democrat Party, should contemplate a name change: to the “anti-Democrats”, perhaps, or the catchier “Born to Rule!”. It is boycotting next month’s election not because it would be unfair (though it might be), but because it would lose. It has not won a general election for more than two decades. Its supporters in the south are outnumbered by those in the north and north-east of the country, who keep on voting in proxies for Thaksin Shinawatra, an exiled former prime minister. The forces that the Born to Rules represent, including much of Thailand’s traditional elite, find this impossible to accept. They are openly campaigning for what amounts to dictatorship, though they do not call it that. Democracy has not worked for the Democrats.

Even if they thought they had some chance of winning an election, they might have had second thoughts after last year’s votes in two of Thailand’s neighbours. The Cambodian opposition resisted the temptation to boycott an election in July. It did surprisingly well in a country where the ruling Cambodian People’s Party still functions in many ways like what it once was, the one party in a one-party state. But, despite an alliance with striking garment-workers, the opposition remains far from power.

In Malaysia, the opposition knew the voting system was biased in favour of the ruling coalition, more than is usual even with a first-past-the-post system. In May it lost the election despite winning the popular vote. Constituencies are gerrymandered, but the opposition alleged further rigging and cried foul. Yet in a relatively mature parliamentary system, it seems tacitly to accept it will have to wait for vindication until the next election.

The Maldivian exception

In a column in need of democratic heroes, here is one nominee: the Maldives’ Mr Nasheed. He was president from 2008 to 2012, succeeding a 30-year dictatorship, but was toppled in a coup. Yet he accepted last year’s perverse electoral defeat graciously. He had an eye, says an adviser, on the long term. Other Asian leaders have yet to realise that the true mark of a democrat is not how he wins power in an election but how he loses it.

Economist.com/blogs/banyan

http://samotalis.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment